Since 1954, when the first successful kidney transplant was conducted by Dr. David Hume and Dr. Joseph Murray at Brigham Hospital in Boston, transplantation has evolved into a sophisticated process coordinated by medical professionals, organ procurement organizations, and hospitals.

Perhaps the most critical feature of the procedure is the application of organ preservation protocols to ensure the delivery of high-quality donor organs. An understanding of the potential effects of hypoxic injury (deprivation of adequate oxygen supply at the tissue level) on donated organs and its prevention by applying organ preservation is a critical factor in a successful transplant.

Furthermore, an organ exchange network has been developed to match the appropriate recipient patient to the best available organ. In 1984 the National Organ Transplant Act (NOTA) was enacted to ensure equitable and efficient distribution of donated organs.

Types of Organ Donations

Transplant organs come from either deceased or living donors.

Deceased Donation

Those who wish to save lives by contributing their organs, eyes, or tissues upon death must be registered as a donor in their state of residence. A deceased donation occurs when a registered donor dies under very specific circumstances, the most common being death in the hospital due to an illness or accident, such as severe head trauma, a brain aneurysm, or a stroke. The organs must also pass a rigorous examination to be qualified for transplantation.

While more than 125 million people are registered as organ donors in the U.S., less than one percent can become donors upon death.

Brain Death Testing

In the case of an accident, the process begins with responding paramedics who conduct rescue efforts after arriving on the scene. Life-saving procedures are continued after emergency vehicles arrive at the hospital. Should these fail to have any effect, doctors run tests to confirm "brain death," defined as the complete and irreversible loss of brain function.

In the case of an accident, the process begins with responding paramedics who conduct rescue efforts after arriving on the scene. Life-saving procedures are continued after emergency vehicles arrive at the hospital. Should these fail to have any effect, doctors run tests to confirm "brain death," defined as the complete and irreversible loss of brain function. In some cases, the heart may still be beating and organs receiving oxygen, but there is no evidence of neurological activity in the brain. Several tests are conducted to confirm the condition: A brain-dead patient will display no gag reflex or corneal reflex. For the donation process to begin, two doctors who are independent of the recovery or transplantation teams are required to declare the patient brain dead.

A donor often remains in intensive care until moved to the operating room, where a biopsy is performed on each organ. A pathologist evaluates the results and determines whether the organs qualify for transplantation. For example, in the case of a kidney, the organ must be free of scars and diabetic damage.

Hospital staff may also maintain the potential donor on a ventilator to support body functions while waiting for the representative of a nearby organ procurement organization (OPO) to arrive at the hospital. There are 58 regional nonprofit OPOs in the U.S. that coordinate the donation process. Specialists or trained hospital staff inform and support the family throughout the process.

Evaluation and Donor Eligibility

The OPO recovery coordinator verifies the patient is a registered donor and reviews the information provided by the hospital. If the deceased is not listed on the registry and has not consented donation in another manner (often indicated on the driver's license), the OPO will request authorization from a close relative.

The OPO recovery coordinator verifies the patient is a registered donor and reviews the information provided by the hospital. If the deceased is not listed on the registry and has not consented donation in another manner (often indicated on the driver's license), the OPO will request authorization from a close relative.Patient evaluation is conducted which includes a medical history, social background, and physical examination to determine if the patient is a suitable candidate for donation.

Organs eligible for transplant include the heart, liver, lungs, pancreas, kidney, and small intestine. Tissues such as the tendons, corneas, and skin are also candidates. Organs are evaluated individually, even those from people who don’t meet ideal health standards, allowing smokers, diabetics, the elderly, and even people with certain cancers to be donors.

The Matching Process

Once donor registration has been confirmed or family consent provided, a clinical coordinator maintains the patient medically with help from hospital personnel. In some cases, a doctor consultation is also required.

When the deceased person's evaluation is satisfactory, the OPO will contact the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN). They are responsible for the national registry of all U.S. patients who have requested a transplant and the transplantation system in the U.S. OPTN is administered by the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS), a non-profit, scientific and educational organization.

The OPO enters the potential donation organ information, the donor's body size and blood type into the UNOS database.

While potential recipients for a transplant are often referred to as being on a waitlist, the group is more accurately defined as a pool. The first-come, first-served patient queue does not always apply because UNOS places similar applicants into the same category. The organization collects information including physical characteristics, age, blood type, protein compatibility, immune system, social history, and more, to determine which donor(s) will be the best match.

While potential recipients for a transplant are often referred to as being on a waitlist, the group is more accurately defined as a pool. The first-come, first-served patient queue does not always apply because UNOS places similar applicants into the same category. The organization collects information including physical characteristics, age, blood type, protein compatibility, immune system, social history, and more, to determine which donor(s) will be the best match. When a donor organ becomes available, the UNOS database generates a dynamic list to determine where and for whom the organs would be most effective. Prioritization may be based on time waiting and location. However, if there is a perfect match of all six human leukocyte antigens (the proteins used as a criterion for matching donor and recipient), a recent applicant, or distant registrant may be selected.

Matching Organs and Recipients

Selection is often based on body size, blood type, life dependency, and time spent in the ‘pool’ of potential recipients. The heart, liver, and lungs are matched by blood type and body size. Genetic tissue type is a factor in matching the pancreas and kidneys.

Once available, each organ is offered to the best-matched potential recipient and their transplant team.

A transplant surgeon must determine if the organ is medically appropriate for the potential recipient. The organ may be refused if, for example, the patient is not healthy enough to be transplanted or cannot be contacted promptly.

Recovering and Transporting Organs

After the qualification process, organs are removed from the body. The surgical team is careful to retain the patient’s physical characteristics during the process so that the family can still recognize their beloved. Per federal law, the physicians removing the organs must not have participated in the donor's care before brain death.

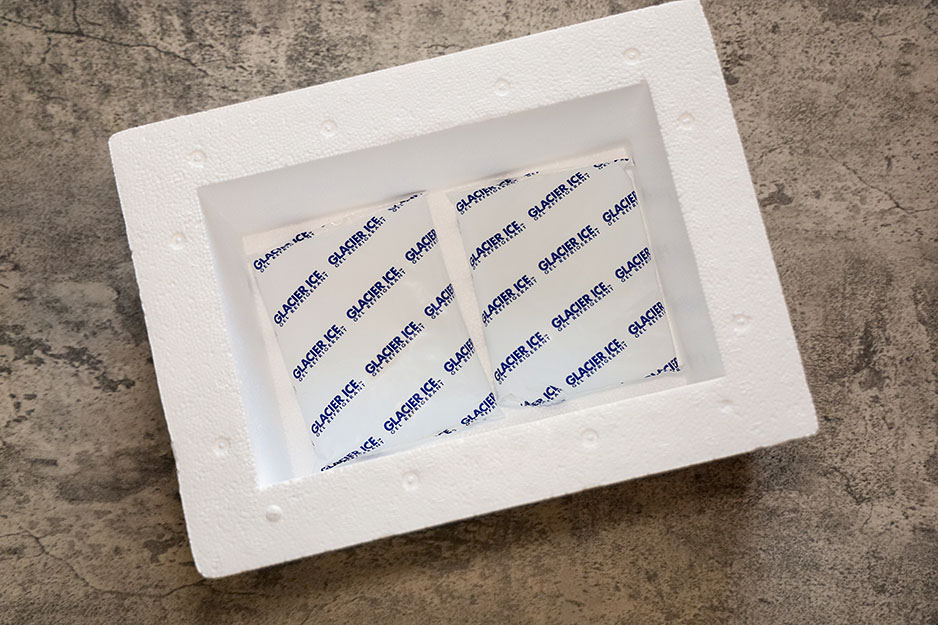

Before removal, a cold preservative solution is pumped into the organ to start the preservation process. Disinfected ice is also inserted into the body cavities to help with cooling. Once the organs are removed from the donor's body, they are packed in sterile containers or a biohazard pouch. The containers are then surrounded by an icy slush mixture to maintain a low temperature without freezing the organs.

Several preservation solutions are available including Eurocollins solution, ViaSpan (University of Wisconsin) Solution, and Custodial among others.

The storage and transport method of all organs except kidneys is based on simple hypothermia. They are kept cold in a preservative solution.

Kidneys are typically placed on a pulsatile perfusion machine that continuously pumps preservation solution through them. This allows transplant surgeons to better assess the suitability of some suspect kidneys. Methods are being developed to perfuse other organs as well, including the heart, liver, and lungs.

Organ Transport

After removal from the donor, organs remain healthy only for a brief period (hence the dramatic run through the hospital hallway). The OPO representative arranges the transportation of the organs to the hospitals of the intended recipients. Type of transportation depends on the distance required and can involve ambulances, helicopters, and commercial airplanes.

Organ Survival Outside of the Body

While kidneys are very tolerant in terms of time to transplant, two days is considered the maximum time to get one up and running inside a recipient's body.

The time limit to remain viable outside of the body differs by organ:

- Heart: 4-6 hours.

- Lung: 4-6 hours.

- Liver: 8-12 hours.

- Pancreas: 12-18 hours.

- Intestines: 8-16 hours.

- Kidney: 24-36 hours.

OPOs use certified couriers to transport organs from hospital to hospital, often via the airport. Most major airlines will ship organs, and they give those flights priority. Flights with transplant organs onboard get moved to the head of the runway queue for takeoff.

Many of the factors considered when matching organs from deceased donors to potential recipients are the same. However, some factors become more important. Some organs can survive outside the body longer than others. Therefore, the transport time between the donor's hospital and the potential recipient's hospital can be a deciding factor.

New Technology for Organ Transport

In 2006, European surgeons successfully transplanted the first heart using the TransMedics Organ Care System, a portable device used for keeping the heart beating with a flow of blood and oxygen during transport. A successful lung transplant was completed in 2011 using a similar transport device.

According to Dr. Abbas Ardehali, director of the heart and lung transplant program at UCLA, there are several benefits to keeping donor organs alive.

Organs that continue to function at near body temperatures, instead of being placed on ice, suffer less damage. Therefore, the recipient's body is more accepting to the new organ, which may improve transplant success rates.

Results from lung transplant studies in the U.S. show the new method reduces primary graft dysfunction, an indicator of how well the new lungs are working. Patients who participated in live organ transplants during the study experienced a lower risk of organ rejection, spent less time on a ventilator, required minimal time in intensive care, and suffered fewer lung-related complications.

The transport system also allows organs to remain outside the body for more time, expanding the geographic region for shared organs.

According to Organdonor.gov, 18 of the more than 100,000 people in the U.S. awaiting an organ die each day without a donation.

Currently, more than 75 percent of donor’s lungs are rejected due to infection or excessive damage. If lungs and other organs can be kept alive outside the body for several days, infections may be treated with antibiotics and improvements made to the organs' resilience.

Transplanting the Organs

When the organ arrives at its destination, receiving transplant surgeons prep the patient and operate. Surgical teams may work long hours to transplant the new organs into the waiting patients.

Typically, recipients only receive basic, anonymous information about their donor, for example, a middle-aged man from a neighboring town.

The Living Donation Process

While most organ donations occur after the donor's death, some tissues and organs can be transplanted from live donors.

Most living organ donations come from family members or close friends. However, some altruistic individuals donate to someone they don’t know.

Typical Living Organ Donations

One kidney is the most commonly donated organ. The donor's remaining kidney functions as required, removing waste from the body.

One lobe of the liver is another common living donation. Cell regeneration in the untouched lobe of the liver returns it to its original size. Re-growth of the liver occurs rapidly in both the donor and recipient.

A complete lung or part of a lung, part of the pancreas, or part of the intestines can also be donated while alive. Both the donated portion of the organ and the portion remaining with the donor are fully functioning, although they do not regenerate.

Living Tissue Donation

Tissues donated by living donors:

- Skin from various surgeries like abdominoplasty.

- Bone from knee or hip replacements.

- Cells from umbilical cord blood and bone marrow.

- Amnion from childbirth.

- White and red blood cells, platelets, and the serum that transports blood cells via the circulatory system.

- A healthy body easily replaces tissues such as blood or bone marrow. Both can even be donated more than once since they are regenerated.

Conclusion

Coupled with a network database of donors and recipients, the transplant process for both deceased and live donors have benefited dramatically from improvements in technology and procedures over the past 60 years. The probability of success has reached an acceptable level and can only improve as new techniques for preserving organs are developed. Saving lives with organ transplants is getting easier.